In this interview with modular master Drew McDowall we talked about his creative processes, dissociative states, the current music scene, and other things.

In this interview with modular master Drew McDowall we talked about his creative processes, dissociative states, the current music scene, and other things.

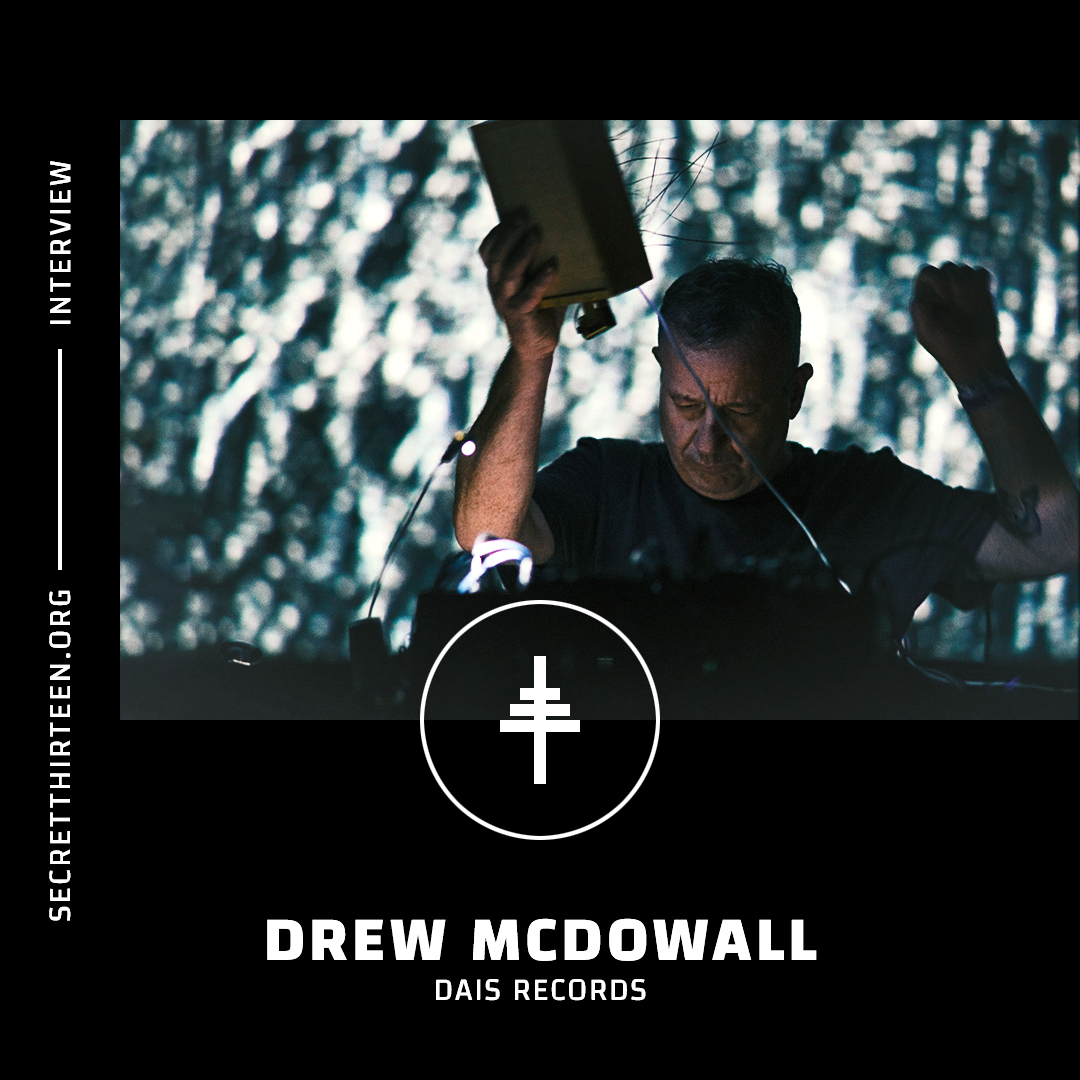

Drew McDowall needs not much further introduction to our readers. Former member of Coil and the architect behind their Time Machines project reemerged as a solo artist a few years back with his modular explorations, which evoke and reflect dissociative states, psychedelic mental landscapes, and hallucinatory moods. His live sets are morphing improvisatory experiences, where every twist could be different each time, immersing the listener in the hypnotic loops and waves of dense atmospheres. His records, which are informed by his live performances, share similar dynamics. His most recent LP, The Third Helix released by Dais Records continues these patterns with brighter drifting tones and undercurrents.

This interview was taken during Drew’s visit to Vilnius to play in the Flatlines event curated by Secret Thirteen. We spoke of the creative processes shaping his sounds, his re-emergence as a solo artist, Time Machines, living in New York, the current state of the experimental music scene and more. For those in Berlin, be sure to catch his upcoming MONOM performance at CTM festival and listen to his recent mix for our journal.

Drew McDowall: So, when I was working on the new live version of Time Machines, on its reinterpretation, it had an intended psychedelic, dissociative effect. I had this feeling that i wanted to do more, that this isn’t done yet, that this is a fertile ground for re-exploring. This psychedelic, hallucinatory, disassociative effect was something I wanted to dive deeper into. And I did not want to do Time Machines 2, I wanted to take that feeling of entrance and describe it musically. So I was definitely inspired by reworking Time Machines and I definitely wanted to do a hallucinatory album. With that comes that ambient feeling, though I think some of the tracks on the record are very dense. The inspiration and genesis of the album was the outline and tracing of various dissociative states I am finding myself in these days.

Drew McDowall: I am really enjoying it, because of the reaction I have been getting. When I perform it live, if it does not have a psychoactive effect on me, then it’s not working, so I have been able to make sure that first and foremost it has the right effect on me, then I am quite confident that the audience will get that experience too. And it has been really interesting getting the audience reactions, meeting people after the show and telling me how it deeply affected them. And being able to do this reinterpretation of Time Machines is hugely satisfying, because a lot of people have not been exposed to that in a live context. And it is also mutating as well.

The first time I did it was in Los Angeles for the Dais Records 10 year anniversary show. That was the point of doing Time Machines live as it was also the 20 year anniversary of the release of the record. So from then until my last show in Athens it changed a lot. People who saw me some months ago said that it had a very different sense. So it has its own life, it mutates regardless of whether I want it to or not. It is not a static thing and never felt like one. It always felt like an entity, that has agency and that I am just pulled along by it. I would not do it if it was just a static recreation of something that happened 20 years ago. That would be boring, I won’t be interested in doing that. So that makes it really enjoyable. I only intended to do it a couple of times, but I have been enjoying it so much.

Drew McDowall: The community has expanded massively. I think people get a warped idea of what experimental/industrial community was like then. It was actually very small. We all felt that we were just working in obscurity, that no one heard what we were doing. That was our default assumption. Now emerged this global community of experimental artists, people doing unquantifiable radically interesting music to a fairly large global audience. I think that is wonderful, I don’t see any downside to that. It feels good that this globally connected community exists.

Also it’s good that people can quickly access what other people are doing. It is always this insane arms race between innovation and experimentation. Because back then you just hear something on a record and eventually you just hear what are your peers doing in another country. And now I can hear it right away. Everyone is taking it to deeper and higher levels. I love the state of where we are right now with experimental music, it feels like a very healthy time. Obviously the technology also changed and that creates interesting innovations, but there are also people reacting against it. There are people who use current technology and people who do the inverse and go back to basics with some cassette loops and a piece of sheet metal.

Drew McDowall: I have always loved collaborating. I never wanted to do anything on a solo basis. When I first came to New York, I could not leave as I was going through this whole green card process. So it meant I couldn’t go back to the UK and work with Coil. That was why we stopped working together as it was becoming impossible for me to go back. So I always had my own studio, where I could work on stuff and then we would take to the Coil studio, where we would develop things from there. But everything that I did in my home studio was with the view that it will be used in some kind of collaboration.

When I was in New York, I started working with my friend Kara Bohnenstiel. We had this project Captain Sons And Daughters and released some seven inches. And then I was also doing collabs as Compound Eye with Tres Warren from Psychic Ills. But at the same time I started to record more and more stuff that was not for collaboration, that really wasn’t for anything until someone asked me to do a live modular set in 2012. I had really no interest in playing a solo live performance, but the person really did not take no for an answer. So I did it and really enjoyed it.

The same night Ryan Martin from Dais Records said, “Let me know if you want to release a record.” I wanted to do more live sets and have that informing the recording process rather than the other way around. Playing those live shows in New York was a really healthy incubating experience, because there were small DIY venues exposed to a lot of people so you could just play around, test what worked and what didn’t. So I really enjoyed that and I felt that the record was taking shape through these live experimentations. That ended up being Collapse, the first record on Dais. So rather than anything really deliberate, it was a fairly organic process which led to the first solo record.

Drew McDowall: It is not so much a rigid criteria rather than a feeling of being a fruitful collaboration. Also I am not very good in doing long distance collaborations. I mean, I like the idea of it and would like to try it more, but most of the collaborations I have was like when we are both physically present in the same space. There is something about that physicality, that I think is really important, when you are playing off to each other in the moment.

I have done some collabs remotely. The one was with Rabit for the penultimate LP, then collaborating with Shapednoise and Rabit for a track for the next Shapednoise record. Those were fruitful collaborations, but they were more one-track. I think for the whole LP it would be different. When I collaborated with Hiro Kone, we basically went up to the mountains and recorded there without any distraction. Collaborating with Puce Mary for some live shows, we just worked together at my studio in Brooklyn. We will start recording an LP and finish it off soon. Going back to your question about the criteria, it is really more that somebody has a similar mindset even though it might work in a different idiom. The music might be different, but the approaches have to be compatible.

Drew McDowall: Everything influences an artist. It is just one of those things. Does the physical space influence me? I can’t say that work that I am doing would be the same if I hadn’t left London. It is hard to quantify how it does. When I moved to New York in the early 2000s. I moved there in 1999, but had a little bit of a hiatus of not making music for 18 months. And when I started, I was really hating what was going on in New York musically, so it was almost like a reaction to that. It was not a very interesting time or I should say there was probably a ton of very interesting stuff going on, but I wasn’t hearing it, so I was just making it myself. There is something about New York that is influential - that intensity of living such a huge metropolis, which is insanely noisy could affect you directly or in an opposite way.

Drew McDowall: You know there is a couple of different elements. Sometimes I start to think about a piece in my brain more architecturally, that it should have a certain shape. Starting to think about timbral elements and possibly rhythmic elements, it almost has a synaesthetic physicality which starts to formulate and then I try to recapture that in the studio. The other way is just sitting in the studio and just enjoying playing with sounds without any purpose. I think that is hugely underrated, because everything is under such time-constraints these days. It’s like we have to do a track, we have to do this and this. Something must be also done about just sitting with your instrument whatever it might be. And just playing it with no purpose, with no end result in mind. And when I do that, it is often the most productive things happen. I am literally just playing around and things all emerge like happy accidents just take form. I actually really love that process. I get lots of ideas when I’m riding my bicycle. That is probably why I have a couple of bike accidents a year. This a really great place to start formulating ideas.

The other good time is in my hypnagogic state. Between waking and sleeping I find a huge well spring of ideas. They are often not necessarily musical, they are just something that I would like to lay into the language that is describable. And for me music is the first stop in that process.

Drew McDowall: Dreams very much so, yes, but I actually think that the hypnagogic, pre-dream state is a more fertile ground for ideas.

I also stopped fighting disassociative states. I always put an enormous amount of energy into not going into those states. Just to try and function like a human being. But now I just go with it, that dissociate freedom. And that’s useful.

Drew McDowall: Yeah, totally. The whole point of Coil (and I try and continue to do it in various ways) is to come up with the methodology, tools and tricks of not having the normal everyday frame of thinking, the normal prosaic mindset, that we are forced into by the demands of work, life, relationships etc. It is good to be able to circumvent that and to find the tools that help you do it more easily.

Drew McDowall: I mean, everything that you do is informed by the world around. It does not have to be explicitly political, art does not have to be anything. But I am not interested in people, who are apolitical, I think in times like this of massive crisis, everyone has to take a stand whether that is reflected in your art or not is another question.

Drew McDowall: Before I was in the band, when I was 13-14 I had some experimental music that accidentally came across like Faust, Can and stuff like that. When I went into punk in 1977, me, my ex-wife Rose McDowall and another guy in the band, we went to see The Clash, when they played in Glasgow in 1977 and they had Suicide opening for them. And Suicide just ripped apart and reconstituted my ideas of what it is to be in a band. The three of us were really impressed. Not that it was going to sound like Suicide, but The Clash sounded just so boring and mediocre in comparison. So definitely Suicide was a huge influence and then a lot of the other things that were happening alongside punk. Things that are now called postpunk, but which were happening before punk. It was just so weird that it was called postpunk, but there was stuff like stuff like This Heat, obviously Throbbing Gristle was a huge influence on an industrial level. Then DIY things such as The Desperate Bicycles. But there was the whole confluence of different things happening that shaped. And one of the biggest things was that I got a reel-to-reel tape deck when I was 16 and I started cutting out tapes without any idea what I was doing, just really loving the loops that would emerge from used tapes from second-hand markets. And I was just cutting them up randomly, making loops. That was my first hands-on experience with random sampling.

Drew McDowall: Oh, yeah, absolutely. I always had some form of modular or semi-modular instrument. Like my first synth that somebody lent me was MS20 or MS10. This was when they first came out in 1978, so for me it is just familiarity, something that I enjoy doing. But if I was locked in a room with a laptop and Max/MSP or something like that, I don’t think I would be too unhappy. I think too much importance gets placed on tools rather than who is behind them. I love modular equipment, I am not playing down its importance, but at the same time I do try not to fetishize it too much. And I know if I did not have it, I would have other means to get to the same place. I mean I see people doing fantastic things with almost no equipment, just with a couple of crappy synths, a couple of effect pedals or just with a laptop or an iPad. People can do fantastic work with whatever tools are available.

Drew McDowall: First of all I met Genesis P-Orridge through Alex Ferguson, who was an early member of Psychic TV. He did some work with Rose’s band Strawberry Switchblade. It was like links in a chain, not even a chain, but almost some kind of rhizomatic, root system. So Genesis was the first person I met in this industrial world. This was during the Psychic TV phase. And then through Genesis I met that person called Bee, which was really influential during the early days of Thee Temple ov Psychick Youth. There is a Coil track called “Bee Has the Photos”. And then through Bee I met David Tibet and he introduced me to John Balance and Peter Christopherson. So there was just different connections. There was obviously no internet then, it was physically meeting someone face-to-face in a cafe. And there was this bar called Bradley’s in London. I don’t even know if it is still there, but they managed to get around the daytime drinking restrictions that London had. So we would all meet almost on any given day. There would be David Tibet, Sleazy, Steven Stapleton, William Bennett, John Balance - the whole bunch of people. And not only just the ones who made music, but all those who were a part of the scene. The whole bunch of London degenerates, which were part of this family. There was no coherent philosophy, everyone was just very different, but drawn together by being outsiders, which had some affinity for each other. It is probably what we had in common.